Can inter-religious encounters bring peace?

3 September 2022, Karlsruhe, Germany: Participants in the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches were able to take part in a variety of Encounters on the weekend, including a visit to the Gardens of Religion project in Karlsruhe, Germany, a project promoting interreligious cooperation and learning. The 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches, taking place in Karlsruhe, Germany 31 August to 8 September. Photo: Simon Chambers/WCC

Workshop explores how interreligious dialogue brings trust and respect

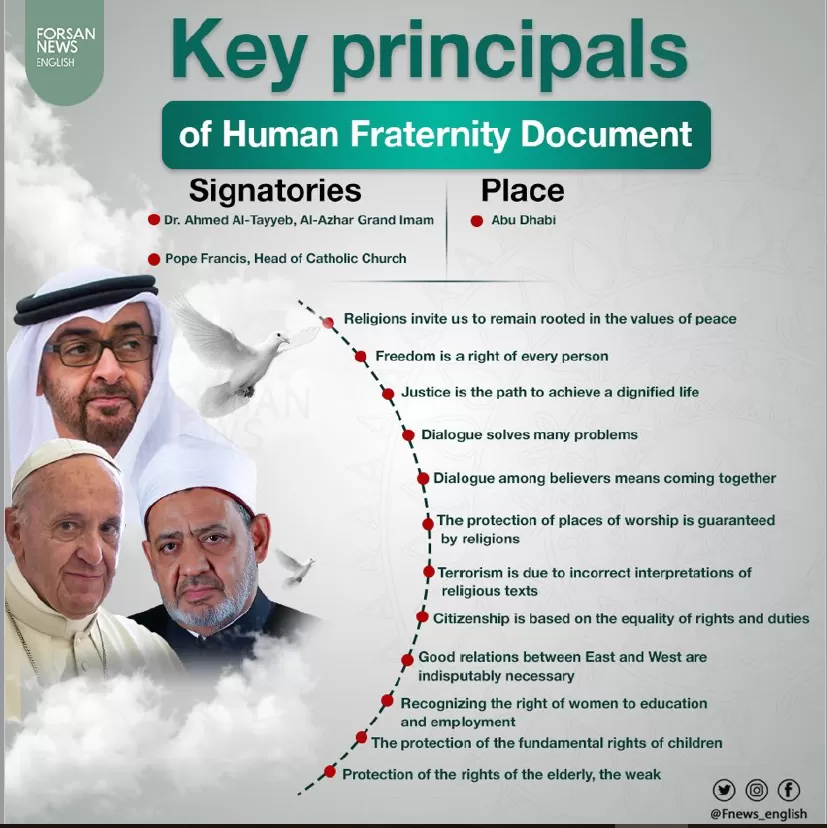

Can inter-religious encounters and dialogue help address challenges and conflicts? Can representatives of different religions act together for peace?

These crucial questions were raised in a workshop, “Participation and peace through interreligious cooperation,” held in the context of the World Council of Churches 11th Assembly in Karlsruhe.

Workshop participants found that nearly every religion speaks about peace—yet many conflicts have occurred or escalated when one group tries to establish its religion as a superior one.

The past decade witnessed an increase in religious tensions and sectarian violence between Hindus and Muslims in India; Sunni and Shia Muslims in the Middle East; and Muslims and Christians in South Sudan and other countries in Africa. In some European countries, violence involving people from minority Muslim groups is behind social tensions and conflicts.

“This workshop is not intended to develop a conceptual analysis on these issues, but to share good practices resulting from two specific experiences: the House of Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in Puttalam, Sri Lanka; and the House of religion – Dialogue of Cultures in Berne, Switzerland,” explained Heinz Bischel, head of department with the Reformed Church Berne-Jura-Solothurn.

Coming together

The idea of the house in Berne came out when migrations brought many different religions into Switzerland, a traditional Christian country.

“We realized these communities, which did not enjoy support from the state, had to come together in houses, garages, and other inadequate places. Why not have a house with a temple where they can practice their religions and engage in interreligious dialogue too?” said Karin Mykytjuk, director of the house.

The House of religion – Dialogue of Cultures in Berne opened officially in 2014, uniting eight different religions. Since then, it has become a place of encounter and recognition. It has given high visibility to religious minorities and offered a platform for ecumenism and interfaith dialogue, thereby fostering societal cohesion and peace.

A safe space

The idea was cherished by Sri Lankan representatives of different religions living in Switzerland.

The 25-year-long civil war which caused between 80,000–100,000 deaths, according to United Nations estimates, called for an interreligious dialogue that can transform cultural violence into cultural peace, said Sasikumar Tharmalingam, a Hindu priest.

“When the idea of creating a space for interfaith dialogue did not receive a favourable reception from religious leaders in Colombia, the Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, and Christian representatives decided to launch the program in Puttalam,” said Fernando Emmanuel, a Roman Catholic priest and one of the leaders of the initiative.

In Puttalam, a 45,000-inhabitant city on the west coast of Sri Lanka, a piece of land was purchased in 2017 and the laying of the foundation stone was celebrated half a year later.

Since its establishment, the House of Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in Puttalam has provided a safe space for representatives of different cultures and religions in Sri Lanka to come together for peacemaking dialogue.

“The encounters have helped forge trust and respect for each other and allowed Tamil and Singhalese young people to be educated on human rights matters,” said Emmanuel.

There was consensus that any process of interfaith dialogue should involve at least three elements: getting to know each other is a fundamental premise to begin grappling with conflicts; healing of wounds in a public and safe space so reconciliation is feasible; and educating the new generations so that prejudices, negative perceptions and stereotypes are eradicated.

Can inter-religious encounters bring peace? Read More »

Jesus in the gospel challenges his host and his friends to extend their horizons and to offer hospitality to people who are not part of their cosy and select little social scene. He challenges them to move out beyond the familiar, to what is strange and unsettling and messy and foreign to them

Jesus in the gospel challenges his host and his friends to extend their horizons and to offer hospitality to people who are not part of their cosy and select little social scene. He challenges them to move out beyond the familiar, to what is strange and unsettling and messy and foreign to them